History of England

| History of England |

|---|

|

|

|

The territory today known as England became inhabited more than 800,000 years ago, as the discovery of stone tools and footprints at Happisburgh in Norfolk have indicated.[1] The earliest evidence for early modern humans in Northwestern Europe, a jawbone discovered in Devon at Kents Cavern in 1927, was re-dated in 2011 to between 41,000 and 44,000 years old.[2] Continuous human habitation in England dates to around 13,000 years ago (see Creswellian), at the end of the Last Glacial Period. The region has numerous remains from the Mesolithic, Neolithic and Bronze Age, such as Stonehenge and Avebury. In the Iron Age, all of Britain south of the Firth of Forth was inhabited by the Celtic people known as the Britons, including some Belgic tribes (e.g. the Atrebates, the Catuvellauni, the Trinovantes, etc.) in the south east. In AD 43 the Roman conquest of Britain began; the Romans maintained control of their province of Britannia until the early 5th century.

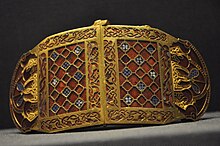

The end of Roman rule in Britain facilitated the Anglo-Saxon settlement of Britain, which historians often regard as the origin of England and of the English people. The Anglo-Saxons, a collection of various Germanic peoples, established several kingdoms that became the primary powers in present-day England and parts of southern Scotland.[3] They introduced the Old English language, which largely displaced the previous Brittonic language. The Anglo-Saxons warred with British successor states in western Britain and the Hen Ogledd (Old North; the Brittonic-speaking parts of northern Britain), as well as with each other. Raids by Vikings became frequent after about AD 800, and the Norsemen settled in large parts of what is now England. During this period, several rulers attempted to unite the various Anglo-Saxon kingdoms, an effort that led to the emergence of the Kingdom of England by the 10th century.

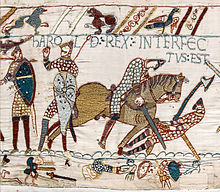

In 1066, a Norman expedition invaded and conquered England. The Norman dynasty, established by William the Conqueror, ruled England for over half a century before the period of succession crisis known as the Anarchy (1135–1154). Following the Anarchy, England came under the rule of the House of Plantagenet, a dynasty which later inherited claims to the Kingdom of France. During this period, Magna Carta was signed and Parliament became established. Anti-Semitism rose to great heights, and in 1290, England became the first country to permanently expel the Jews.[4][5][6][7] A succession crisis in France led to the Hundred Years' War (1337–1453), a series of conflicts involving the peoples of both nations. Following the Hundred Years' Wars, England became embroiled in its own succession wars between the descendants of Edward III's five sons. The Wars of the Roses broke out in 1455 and pitted the descendants of the second son (through a female line) Lionel of Antwerp known as the House of York against the House of Lancaster who descended from the third son John of Gaunt and his son Henry IV, the latter of whom had overthrown his cousin Richard II (the only surviving son of Edward III"s eldest son Edward the Black Prince) in 1399. In 1485, the war ended when Lancastrian Henry Tudor emerged victorious from the Battle of Bosworth Field and married the senior female Yorkist descendant, Elizabeth of York, uniting the two houses.

Under the Tudors and the later Stuart dynasty, England became a colonial power. During the rule of the Stuarts, the English Civil War took place between the Parliamentarians and the Royalists, which resulted in the execution of King Charles I (1649) and the establishment of a series of republican governments—first, a Parliamentary republic known as the Commonwealth of England (1649–1653), then a military dictatorship under Oliver Cromwell known as the Protectorate (1653–1659). The Stuarts returned to the restored throne in 1660, though continued questions over religion and power resulted in the deposition of another Stuart king, James II, in the Glorious Revolution (1688). England, which had subsumed Wales in the 16th century under Henry VIII, united with Scotland in 1707 to form a new sovereign state called Great Britain.[8][9][10] Following the Industrial Revolution, which started in England, Great Britain ruled a colonial Empire, the largest in recorded history. Following a process of decolonisation in the 20th century, mainly caused by the weakening of Great Britain's power in the two World Wars; almost all of the empire's overseas territories became independent countries.

Prehistory

[edit]Stone Age

[edit]

The time from Britain's first inhabitation until the Last Glacial Maximum is known as the Old Stone Age, or Palaeolithic era. Archaeological evidence indicates that what was to become England was colonised by humans long before the rest of the British Isles because of its more hospitable climate between and during the various glacial periods of the distant past. This earliest evidence, from Happisburgh in Norfolk, includes the oldest hominid artefacts found in Britain, and points to dates of more than 800,000 RCYBP.[1] These earliest inhabitants were hunter-gatherers. Low sea-levels meant that Britain was attached to the continent for much of this earliest period of history, and varying temperatures over tens of thousands of years meant that it was not always inhabited.[11]

England has been continuously inhabited since the last Ice Age ended around 9000 BC, the beginning of the Middle Stone Age, or Mesolithic era. Rising sea-levels cut off Britain from the continent for the last time around 6500 BC. The population by then, as in the rest of the world, was exclusively anatomically modern humans, and the evidence suggests that their societies were increasingly complex and they were manipulating their environment and prey in new ways, possibly selective burning of then omnipresent woodland to create clearings for herds to gather and then hunt them. Hunting was mainly done with simple projectile weapons such as javelin and possibly sling. Bow and arrow was known in Western Europe since at least 9000 BC. The climate continued to warm and the population probably rose.[12]

The New Stone Age, or Neolithic era, began with the introduction of farming, ultimately from the Middle East, around 4000 BC. It is not known whether this was caused by a substantial folk movement or native adoption of foreign practices or both. People began to lead a more settled lifestyle. Monumental collective tombs were built for the dead in the form of chambered cairns and long barrows. Towards the end of the period, other kinds of monumental stone alignments begin to appear, such as Stonehenge; their cosmic alignments show a preoccupation with the sky and planets. Flint technology produced a number of highly artistic pieces as well as purely practical. More extensive woodland clearance was done for fields and pastures. The Sweet Track in the Somerset Levels is one of the oldest timber trackways known in Northern Europe and among the oldest roads in the world, dated by dendrochronology to the winter of 3807–3806 BC; it is thought to have been a primarily religious structure.[11] Archaeological evidence from North Yorkshire indicates that salt was being manufactured there in the Neolithic.[13]

Later Prehistory

[edit]Bronze Age

[edit]

The Bronze Age began around 2500 BC with the appearance of bronze objects. This coincides with the appearance of the characteristic Bell Beaker culture, following migration of new people from the continent. According to Olalde et al. (2018), after 2500 BC Britain's Neolithic population was largely replaced by this new Bell Beaker population, that was genetically related to the Corded Ware culture of central and eastern Europe and the Yamnaya culture of the eastern European Pontic-Caspian Steppe.[14][15] While the migration of these Beaker peoples must have been accompanied by a language shift, the Celtic languages were probably introduced by later Celtic migrations.[16]

The Bronze Age saw a shift of emphasis from the communal to the individual, and the rise of increasingly powerful elites whose power came from their prowess as hunters and warriors and their controlling the flow of precious resources to manipulate tin and copper into high-status bronze objects such as swords and axes. Settlement became increasingly permanent and intensive. Towards the end of the Bronze Age, many examples of very fine metalwork began to be deposited in rivers, presumably for ritual reasons and perhaps reflecting a progressive change in emphasis from the sky to the earth, as a rising population put increasing pressure on the land. England largely became bound up with the Atlantic trade system, which created a cultural continuum over a large part of Western Europe.[17] It is possible that the Celtic languages developed or spread to England as part of this system; by the end of the Iron Age there is much evidence that they were spoken across all England and western parts of Britain.[18]

Iron Age

[edit]

The Iron Age is conventionally said to begin around 800 BC. At this time, the Britons or Celtic Britons were settled in England. The Celtic people of early England were the majority of the population, beside other smaller ethnic groups in Great Britain. They existed like this from the British Iron Age into the Middle Ages, when it was overtaken by Germanic Anglo-Saxons. After some time, the Celtic Britons diverged into the multiple distinct ethnic groups such as Welsh, Cornish and Breton, but they were still tied by language, religion and culture. They spoke the Brittonic language, a Celtic language which is the ancestor of the modern Brittonic languages. The Atlantic trade system had by this time effectively collapsed, although England maintained contacts across the channel with France, as the Hallstatt culture became widespread across the country. Its continuity suggests it was not accompanied by substantial movement of population; crucially, only a single Hallstatt burial is known from Britain, and even here the evidence is inconclusive. On the whole, burials largely disappear across England, and the dead were disposed of in a way which is archaeologically invisible: excarnation is a widely cited possibility. Hillforts were known since the Late Bronze Age, but a huge number were constructed during 600–400 BC, particularly in the South, while after about 400 BC new forts were rarely built and many ceased to be regularly inhabited, while a few forts become more and more intensively occupied, suggesting a degree of regional centralisation.

Around this time the earliest mentions of Britain appear in the annals of history. The first historical mention of the region is from the Massaliote Periplus, a sailing manual for merchants thought to date to the 6th century BC, and Pytheas of Massilia wrote of his voyage of discovery to the island around 325 BC. Both of these texts are now lost; although quoted by later writers, not enough survives to inform the archaeological interpretation to any significant degree.

Britain, we are told, is inhabited by tribes which are autochthonous and preserve in their ways of living the ancient manner of life. They use chariots, for instance, in their wars, even as tradition tells us the old Greek heroes did in the Trojan War.

Contact with the continent was less than in the Bronze Age but still significant. Goods continued to move to England, with a possible hiatus around 350 to 150 BC. There were a few armed invasions of hordes of migrating Celts. There are two known invasions. Around 300 BC, a group from the Gaulish Parisii tribe apparently took over East Yorkshire, establishing the highly distinctive Arras culture. And from around 150–100 BC, groups of Belgae began to control significant parts of the South.

These invasions constituted movements of a few people who established themselves as a warrior elite atop existing native systems, rather than replacing them. The Belgic invasion was much larger than the Parisian settlement, but the continuity of pottery style shows that the native population remained in place. Yet, it was accompanied by significant socio-economic change. Proto-urban, or even urban settlements, known as oppida, begin to eclipse the old hillforts, and an elite whose position is based on battle prowess and the ability to manipulate resources re-appears much more distinctly.[21]

In 55 and 54 BC, Julius Caesar, as part of his campaigns in Gaul, invaded Britain and claimed to have scored a number of victories, but he never penetrated further than Hertfordshire and could not establish a province. However, his invasions mark a turning-point in British history. Control of trade, the flow of resources and prestige goods, became ever more important to the elites of Southern Britain; Rome steadily became the biggest player in all their dealings, as the provider of great wealth and patronage. In retrospect, a full-scale invasion and annexation was inevitable.[22]

Roman Britain

[edit]

After Caesar's expeditions, the Romans began a serious and sustained attempt to conquer Britain in AD 43, at the behest of Emperor Claudius. They landed in Kent with four legions and defeated two armies led by the kings of the Catuvellauni tribe, Caratacus and Togodumnus, in battles at the Medway and the Thames. Togodumnus was killed, and Caratacus fled to Wales. The Roman force, led by Aulus Plautius, waited for Claudius to come and lead the final march on the Catuvellauni capital at Camulodunum (modern Colchester), before he returned to Rome for his triumph. The Catuvellauni held sway over most of the southeastern corner of England; eleven local rulers surrendered, a number of client kingdoms were established, and the rest became a Roman province with Camulodunum as its capital.[23] Over the next four years, the territory was consolidated and the future emperor Vespasian led a campaign into the Southwest where he subjugated two more tribes. By AD 54 the border had been pushed back to the Severn and the Trent, and campaigns were underway to subjugate Northern England and Wales.

But in AD 60, under the leadership of the warrior-queen Boudicca, the tribes rebelled against the Romans. At first, the rebels had great success. They burned Camulodunum, Londinium and Verulamium (modern-day Colchester, London and St. Albans respectively) to the ground. There is some archaeological evidence that the same happened at Winchester. The Second Legion Augusta, stationed at Exeter, refused to move for fear of revolt among the locals. Londinium governor Suetonius Paulinus evacuated the city before the rebels sacked and burned it; the fire was so hot that a ten-inch layer of melted red clay remains 15 feet below London's streets.[24] In the end, the rebels were said to have killed 70,000 Romans and Roman sympathisers. Paulinus gathered what was left of the Roman army. In the decisive battle, 10,000 Romans faced nearly 100,000 warriors somewhere along the line of Watling Street, at the end of which Boudicca was utterly defeated. It was said that 80,000 rebels were killed, but only 400 Romans.

Over the next 20 years, the borders expanded slightly, but the governor Agricola incorporated into the province the last pockets of independence in Wales and Northern England. He also led a campaign into Scotland which was recalled by Emperor Domitian. The border gradually formed along the Stanegate road in Northern England, solidified by Hadrian's Wall built in AD 138, despite temporary forays into Scotland. The Romans and their culture stayed in charge for 350 years. Traces of their presence are ubiquitous throughout England.

Anglo-Saxon period

[edit]Anglo-Saxon migrations

[edit]

In the wake of the breakdown of Roman rule in Britain from the middle of the fourth century, present day England was progressively settled by Germanic groups. Collectively known as the Anglo-Saxons, these included Angles, Saxons, Jutes and Frisians. The Battle of Deorham was critical in establishing Anglo-Saxon rule in 577.[25] Saxon mercenaries existed in Britain since before the late Roman period, but the main influx of population probably happened after the fifth century. The precise nature of these invasions is not fully known; there are doubts about the legitimacy of historical accounts due to a lack of archaeological finds. Gildas' De Excidio et Conquestu Britanniae, composed in the 6th century, states that when the Roman army departed the Isle of Britannia in the 4th century AD, the indigenous Britons were invaded by Picts, their neighbours to the north (now Scotland) and the Scots (now Ireland). Britons invited the Saxons to the island to repel them but after they vanquished the Scots and Picts, the Saxons turned against the Britons.

Seven kingdoms are traditionally identified as being established by these migrants. Three were clustered in the South east: Sussex, Kent and Essex. The Midlands were dominated by the kingdoms of Mercia and East Anglia. To the north was Northumbria which unified two earlier kingdoms, Bernicia and Deira. Other smaller kingdoms seem to have existed as well, such as Lindsey in what is now Lincolnshire, and the Hwicce in the southwest. Eventually, the kingdoms were dominated by Northumbria and Mercia in the 7th century, Mercia in the 8th century and then Wessex in the 9th century. Northumbria eventually extended its control north into Scotland and west into Wales. It also subdued Mercia whose first powerful King, Penda, was killed by Oswy in 655. Northumbria's power began to wane after 685 with the defeat and death of its king Aegfrith at the hands of the Picts. Mercian power reached its peak under the rule of Offa, who from 785 had influence over most of Anglo-Saxon England. Since Offa's death in 796, the supremacy of Wessex was established under Egbert who extended control west into Cornwall before defeating the Mercians at the Battle of Ellendun in 825. Four years later, he received submission and tribute from the Northumbrian king, Eanred.[26]

Since so few contemporary sources exist, the events of the fifth and sixth centuries are difficult to ascertain. As such, the nature of the Anglo-Saxon settlements is debated by historians, archaeologists and linguists. The traditional view, that the Anglo-Saxons drove the Romano-British inhabitants out of what is now England, was subject to reappraisal in the later twentieth century. One suggestion is that the invaders were smaller in number, drawn from an elite class of male warriors that gradually acculturated the natives.[27][28][29]

An emerging view is that the scale of the Anglo-Saxon settlement varied across England, and that as such it cannot be described by any one process in particular. Mass migration and population shift seem to be most applicable in the core areas of settlement such as East Anglia and Lincolnshire,[30][31][32][33][34] while in more peripheral areas to the northwest, much of the native population likely remained in place as the incomers took over as elites.[35][36] In a study of place names in northeastern England and southern Scotland, Bethany Fox concluded that Anglian migrants settled in large numbers in river valleys, such as those of the Tyne and the Tweed, with the Britons in the less fertile hill country becoming acculturated over a longer period. Fox interprets the process by which English came to dominate this region as "a synthesis of mass-migration and elite-takeover models."[37]

Genetic markers of Anglo-Saxon migrations

[edit]

Genetic testing has been used to find evidence of large scale immigration of Germanic peoples into England. Weale et al. (2002) found that English Y DNA data showed signs of a mass Anglo-Saxon immigration from the European continent, affecting 50%–100% of the male gene pool in central England. This was based on the similarity of the DNA collected from small English towns to that found in Friesland.[38] A 2003 study with samples coming from larger towns, found a large variance in amounts of continental "Germanic" ancestry in different parts of England.[39] In the study, such markers typically ranged from 20% and 45% in southern England, with East Anglia, the east Midlands, and Yorkshire having over 50%. North German and Danish genetic frequencies were indistinguishable, thus precluding any ability to distinguish between the genetic influence of the Anglo-Saxon source populations and the later, and better documented, influx of Danish Vikings.[40] The mean value of continental Germanic genetic input in this study was calculated at 54 per cent.[41]

In response to arguments, such as those of Stephen Oppenheimer[42] and Bryan Sykes, that the similarity between English and continental Germanic DNA could have originated from earlier prehistoric migrations, researchers have begun to use data collected from ancient burials to ascertain the level of Anglo-Saxon contribution to the modern English gene pool. Two studies published in 2016, based on data collected from skeletons found in Iron Age, Roman and Anglo-Saxon era graves in Cambridgeshire and Yorkshire, concluded that the ancestry of the modern English population contains large contributions from both Anglo-Saxon migrants and Romano-British natives.[43][44]

Heptarchy and Christianisation

[edit]

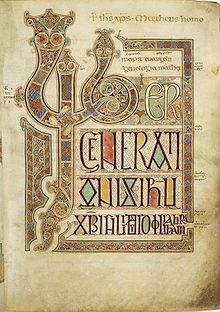

Christianisation of Anglo-Saxon England began around 600 AD, influenced by Celtic Christianity from the northwest and the Roman Catholic Church from the southeast. Augustine, the first Archbishop of Canterbury, took office in 597. In 601, he baptised the first Christian Anglo-Saxon king, Æthelberht of Kent. The last pagan Anglo-Saxon king, Penda of Mercia, died in 655. The last pagan Jutish king, Arwald of the Isle of Wight was killed in 686. The Anglo-Saxon mission on the continent took off in the 8th century, leading to the Christianisation of practically all of the Frankish Empire by 800.

Throughout the 7th and 8th centuries, power fluctuated between the larger kingdoms. Bede records Æthelberht of Kent as being dominant at the close of the 6th century, but power seems to have shifted northwards to the kingdom of Northumbria, which was formed from the amalgamation of Bernicia and Deira. Edwin of Northumbria probably held dominance over much of Britain, though Bede's Northumbrian bias should be kept in mind. Due to succession crises, Northumbrian hegemony was not constant, and Mercia remained a very powerful kingdom, especially under Penda. Two defeats ended Northumbrian dominance: the Battle of the Trent in 679 against Mercia, and Nechtanesmere in 685 against the Picts.[45]

The so-called "Mercian Supremacy" dominated the 8th century, though it was not constant. Aethelbald and Offa, the two most powerful kings, achieved high status; indeed, Offa was considered the overlord of south Britain by Charlemagne. His power is illustrated by the fact that he summoned the resources to build Offa's Dyke. However, a rising Wessex, and challenges from smaller kingdoms, kept Mercian power in check, and by the early 9th century the "Mercian Supremacy" was over. This period has been described as the Heptarchy, though this term has now fallen out of academic use. The term arose because the seven kingdoms of Northumbria, Mercia, Kent, East Anglia, Essex, Sussex and Wessex were the main polities of south Britain. Other small kingdoms were also politically important across this period: Hwicce, Magonsaete, Lindsey and Middle Anglia.[46]

Viking challenge and the rise of Wessex

[edit]

The first recorded landing of Vikings took place in 787 in Dorsetshire, on the south-west coast.[47] The first major attack in Britain was in 793 at Lindisfarne monastery as given by the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle. However, by then the Vikings were almost certainly well-established in Orkney and Shetland, and many other non-recorded raids probably occurred before this. Records do show the first Viking attack on Iona taking place in 794. The arrival of the Vikings (in particular the Danish Great Heathen Army) upset the political and social geography of Britain and Ireland. In 867 Northumbria fell to the Danes; East Anglia fell in 869. Though Wessex managed to contain the Vikings by defeating them at Ashdown in 871, a second invading army landed, leaving the Saxons on a defensive footing. At much the same time, Æthelred, king of Wessex died and was succeeded by his younger brother Alfred. Alfred was immediately confronted with the task of defending Wessex against the Danes. He spent the first five years of his reign paying the invaders off. In 878, Alfred's forces were overwhelmed at Chippenham in a surprise attack.[48]

It was only now, with the independence of Wessex hanging by a thread, that Alfred emerged as a great king. In May 878 he led a force that defeated the Danes at Edington. The victory was so complete that the Danish leader, Guthrum, was forced to accept Christian baptism and withdraw from Mercia. Alfred then set about strengthening the defences of Wessex, building a new navy—60 vessels strong. Alfred's success bought Wessex and Mercia years of peace and sparked economic recovery in previously ravaged areas.[49]

Alfred's success was sustained by his son Edward, whose decisive victories over the Danes in East Anglia in 910 and 911 were followed by a crushing victory at Tempsford in 917. These military gains allowed Edward to fully incorporate Mercia into his kingdom and add East Anglia to his conquests. Edward then set about reinforcing his northern borders against the Danish kingdom of Northumbria. Edward's rapid conquest of the English kingdoms meant Wessex received homage from those that remained, including Gwynedd in Wales and Scotland. His dominance was reinforced by his son Æthelstan, who extended the borders of Wessex northward, in 927 conquering the Kingdom of York and leading a land and naval invasion of Scotland. These conquests led to his adopting the title 'King of the English' for the first time.

The dominance and independence of England was maintained by the kings that followed. It was not until 978 and the accession of Æthelred the Unready that the Danish threat resurfaced. Two powerful Danish kings (Harold Bluetooth and later his son Sweyn) both launched devastating invasions of England. Anglo-Saxon forces were resoundingly defeated at Maldon in 991. More Danish attacks followed, and their victories were frequent. Æthelred's control over his nobles began to falter, and he grew increasingly desperate. His solution was to pay off the Danes: for almost 20 years he paid increasingly large sums to the Danish nobles to keep them from English coasts. These payments, known as Danegelds, crippled the English economy.[50]

Æthelred then made an alliance with Normandy in 1001 through marriage to the Duke's daughter Emma, in the hope of strengthening England. Then he made a great error: in 1002 he ordered the massacre of all the Danes in England. In response, Sweyn began a decade of devastating attacks on England. Northern England, with its sizable Danish population, sided with Sweyn. By 1013, London, Oxford, and Winchester had fallen to the Danes. Æthelred fled to Normandy and Sweyn seized the throne. Sweyn suddenly died in 1014, and Æthelred returned to England, confronted by Sweyn's successor, Cnut. However, in 1016, Æthelred also suddenly died. Cnut swiftly defeated the remaining Saxons, killing Æthelred's son Edmund in the process. Cnut seized the throne, crowning himself King of England.[51]

English unification

[edit]

Alfred of Wessex died in 899 and was succeeded by his son Edward the Elder. Edward, and his brother-in-law Æthelred of (what was left of) Mercia, began a programme of expansion, building forts and towns on an Alfredian model. On Æthelred's death, his wife (Edward's sister) Æthelflæd ruled as "Lady of the Mercians" and continued expansion. It seems Edward had his son Æthelstan brought up in the Mercian court. On Edward's death, Æthelstan succeeded to the Mercian kingdom, and, after some uncertainty, Wessex.

Æthelstan continued the expansion of his father and aunt and was the first king to achieve direct rulership of what we would now consider England. The titles attributed to him in charters and on coins suggest a still more widespread dominance. His expansion aroused ill-feeling among the other kingdoms of Britain, and he defeated a combined Scottish-Viking army at the Battle of Brunanburh. However, the unification of England was not a certainty. Under Æthelstan's successors Edmund and Eadred the English kings repeatedly lost and regained control of Northumbria. Nevertheless, Edgar, who ruled the same expanse as Æthelstan, consolidated the kingdom, which remained united thereafter.

England under the Danes and the Norman conquest

[edit]There were renewed Scandinavian attacks on England at the end of the 10th century. Æthelred ruled a long reign but ultimately lost his kingdom to Sweyn of Denmark, though he recovered it following the latter's death. However, Æthelred's son Edmund II Ironside died shortly afterwards, allowing Cnut, Sweyn's son, to become king of England. Under his rule the kingdom became the centre of government for the North Sea empire which included Denmark and Norway.

Cnut was succeeded by his sons, but in 1042 the native dynasty was restored with the accession of Edward the Confessor. Edward's failure to produce an heir caused a furious conflict over the succession on his death in 1066. His struggles for power against Godwin, Earl of Wessex, the claims of Cnut's Scandinavian successors, and the ambitions of the Normans whom Edward introduced to English politics to bolster his own position caused each to vie for control of Edward's reign.

Harold Godwinson became king, probably appointed by Edward on his deathbed and endorsed by the Witan. But William of Normandy, Harald Hardråde (aided by Harold Godwin's estranged brother Tostig) and Sweyn II of Denmark all asserted claims to the throne. By far the strongest hereditary claim was that of Edgar the Ætheling, but due to his youth and apparent lack of powerful supporters, he did not play a major part in the struggles of 1066, although he was made king for a short time by the Witan after the death of Harold Godwinson.

In September 1066, Harald III of Norway and Earl Tostig landed in Northern England with a force of around 15,000 men and 300 longships. Harold Godwinson defeated the invaders and killed Harald III of Norway and Tostig at the Battle of Stamford Bridge. On 28 September 1066, William of Normandy invaded England in a campaign called the Norman Conquest. After marching from Yorkshire, Harold's exhausted army was defeated and Harold was killed at the Battle of Hastings on 14 October. Further opposition to William in support of Edgar the Ætheling soon collapsed, and William was crowned king on Christmas Day 1066. For five years, he faced a series of rebellions in various parts of England and a half-hearted Danish invasion, but he subdued them and established an enduring regime.

Norman England

[edit]

The Norman Conquest led to a profound change in the history of the English state. William ordered the compilation of the Domesday Book, a survey of the entire population and their lands and property for tax purposes, which reveals that within 20 years of the conquest the English ruling class had been almost entirely dispossessed and replaced by Norman landholders, who monopolised all senior positions in the government and the Church. William and his nobles spoke and conducted court in Norman French, in both Normandy and England. The use of the Anglo-Norman language by the aristocracy endured for centuries and left an indelible mark in the development of modern English.

Upon being crowned, on Christmas Day 1066, William immediately began consolidating his power. By 1067, he faced revolts on all sides and spent four years crushing them. He then imposed his superiority over Scotland and Wales, forcing them to recognise him as overlord.[52] Economic growth and state finances were aided by the beginning of Jewish settlement in London.[53]

The English Middle Ages were characterised by civil war, international war, occasional insurrection, and widespread political intrigue among the aristocratic and monarchic elite. England was more than self-sufficient in cereals, dairy products, beef and mutton. Its international economy was based on wool trade, in which wool from the sheepwalks of northern England was exported to the textile cities of Flanders, where it was worked into cloth. Medieval foreign policy was as much shaped by relations with the Flemish textile industry as it was by dynastic adventures in western France. An English textile industry was established in the 15th century, providing the basis for rapid English capital accumulation.

Henry I, the fourth son of William I the Conqueror, succeeded his elder brother William II as King of England in 1100. Henry was also known as "Henry Beauclerc" because he received a formal education, unlike his older brother and heir apparent William who got practical training to be king. Henry worked hard to reform and stabilise the country and smooth the differences between the Anglo-Saxon and Anglo-Norman societies. The loss of his son, William Adelin, in the wreck of the White Ship in November 1120, undermined his reforms. This problem regarding succession cast a long shadow over English history.

Henry I had required the leading barons, ecclesiastics and officials in Normandy and England, to take an oath to accept Matilda (also known as Empress Maud, Henry I's daughter) as his heir. England was far less than enthusiastic to accept an outsider, and a woman, as their ruler. There is some evidence that Henry was unsure of his own hopes and the oath to make Matilda his heir. Probably Henry hoped Matilda would have a son and step aside as Queen Mother. Upon Henry's death, the Norman and English barons ignored Matilda's claim to the throne, and thus through a series of decisions, Stephen, Henry's favourite nephew, was welcomed by many in England and Normandy as their new king.

On 22 December 1135, Stephen was anointed king with implicit support by the church and nation. Matilda and her own son waited in France until she sparked the civil war from 1139 to 1153 known as the Anarchy. In the autumn of 1139, she invaded England with her illegitimate half-brother Robert of Gloucester. Her husband, Geoffroy V of Anjou, conquered Normandy but did not cross the channel to help his wife. During this breakdown of central authority, nobles built adulterine castles (i.e. castles erected without government permission), which were hated by the peasants, who were forced to build and maintain them.

Stephen was captured, and his government fell. Matilda was proclaimed queen but was soon at odds with her subjects and was expelled from London. The war continued until 1148, when Matilda returned to France. Stephen reigned unopposed until his death in 1154, although his hold on the throne was uneasy. As soon as he regained power, he began to demolish the adulterine castles, but kept a few castles standing, which put him at odds with his heir. His contested reign, civil war, and lawlessness saw a major swing in power towards feudal barons. In trying to appease Scottish and Welsh raiders, he handed over large tracts of land.

Plantagenet Empire

[edit]The first Angevins

[edit]

Empress Matilda and Geoffrey's son, Henry, resumed the invasion; he was already Count of Anjou, Duke of Normandy and Duke of Aquitaine when he landed in England. When Stephen's son and heir apparent Eustace died in 1153, Stephen made an agreement with Henry of Anjou (who became Henry II) to succeed Stephen and guarantee peace between them. The union was retrospectively named the Angevin Empire. Henry II destroyed the remaining adulterine castles and expanded his power through various means and to different levels into Ireland, Scotland, Wales, Flanders, Nantes, Brittany, Quercy, Toulouse, Bourges and Auvergne.[54]

The reign of Henry II represents a reversion in power from the barony to the monarchical state in England; it also saw a similar redistribution of legislative power from the Church, again to the monarchical state. This period also presaged a properly constituted legislation and a radical shift away from feudalism. In his reign, new Anglo-Angevin and Anglo-Aquitanian aristocracies developed, though not to the same degree as the Anglo-Norman once did, and the Norman nobles interacted with their French peers.[55]

Henry's successor, Richard I "the Lion Heart" (also known as "the absent king"), was preoccupied with foreign wars, taking part in the Third Crusade, being captured while returning and pledging fealty to the Holy Roman Empire as part of his ransom,[56] and defending his French territories against Philip II of France.[57] His successor, his younger brother John, lost much of those territories including Normandy following the disastrous Battle of Bouvines in 1214,[58] despite having in 1212 made the Kingdom of England a tribute-paying vassal of the Holy See,[59] which it remained until the 14th century when the Kingdom rejected the overlordship of the Holy See and re-established its sovereignty.[60] The first anti-Semitic pogroms occurred in the wake of Richard's crusades, in 1189–90, in York and elsewhere. In York, 150 Jews died.[61] From 1212 onwards, John had a constant policy of maintaining close relations with the Pope, which partially explains how he persuaded the Pope to reject the legitimacy of Magna Carta.[62]

Magna Carta

[edit]

Over the course of his reign, a combination of higher taxes, unsuccessful wars and conflict with the Pope made King John unpopular with his barons. In 1215, some of the most important barons rebelled against him. He met their leaders along with their French and Scot allies at Runnymede, near London on 15 June 1215 to seal the Great Charter (Magna Carta in Latin), which imposed legal limits on the king's personal powers. But as soon as hostilities ceased, John received approval from the Pope to break his word because he had made it under duress. This provoked the First Barons' War and a French invasion by Prince Louis of France invited by a majority of the English barons to replace John as king in London in May 1216. John travelled around the country to oppose the rebel forces, directing, among other operations, a two-month siege of the rebel-held Rochester Castle.[63]

Henry III

[edit]

John's son, Henry III, was only 9 years old when he became king (1216–1272). He spent much of his reign fighting the barons over Magna Carta[64] and the royal rights, and was eventually forced to call the first "parliament" in 1264. He was also unsuccessful on the continent, where he endeavoured to re-establish English control over Normandy, Anjou, and Aquitaine.[65][66]

His reign was punctuated by many rebellions and civil wars, often provoked by incompetence and mismanagement in government and Henry's perceived over-reliance on French courtiers (thus restricting the influence of the English nobility). One of these rebellions—led by a disaffected courtier, Simon de Montfort—was notable for its assembly of one of the earliest precursors to Parliament. In addition to fighting the Second Barons' War, Henry III made war against Louis IX and was defeated during the Saintonge War, yet Louis did not capitalise on his victory, respecting his opponent's rights.[65]

Henry III's policies towards Jews began with relative tolerance, but became gradually more restrictive. In 1253 the Statute of Jewry reinforced physical segregation and demanded a previously notional requirement to wear square white badges.[67] Henry III also backed an accusation of child murder in Lincoln, ordering a Jew Copin to be executed and 91 Jews to be arrested for trial; 18 were killed. Popular superstitious fears were fuelled, and Catholic theological hostility combined with Baronial abuse of loan arrangements, resulting in Simon de Montfort's supporters targeting of Jewish communities in their revolt. This hostility, violence and controversy was the background to the increasingly oppressive measures that followed under Edward I.[68]

14th century

[edit]

The reign of Edward I (reigned 1272–1307) was rather more successful. Edward enacted numerous laws strengthening the powers of his government, and he summoned the first officially sanctioned Parliaments of England (such as his Model Parliament).[69] He conquered Wales[70] and attempted to use a succession dispute to gain control of the Kingdom of Scotland, though this developed into a costly and drawn-out military campaign.

Edward I is also known for his policies first persecuting Jews, particularly the 1275 Statute of the Jewry. This banned Jews from their previous role in making loans, and demanded that they work as merchants, farmers, craftsmen or soldiers. This was unrealistic, and failed.[71] Edward's solution was to expel Jews from England.[68][72][73] This was the first statewide, permanent expulsion in Europe.[4][74][75][7]

His son, Edward II, was considered a disaster by other nobles. A man who preferred to engage in activities like thatching and ditch-digging[76] and associating with the lower class rather than the activities considered appropriate for the upper class such as jousting, hunting, or the usual entertainments of kings, he spent most of his reign trying in vain to control the nobility, who in return showed continual hostility to him. Meanwhile, the Scottish leader Robert Bruce began retaking all the territory conquered by Edward I. In 1314, the English army was disastrously defeated by the Scots at the Battle of Bannockburn. Edward also showered favours on his companion Piers Gaveston, a knight of humble birth. While it has been widely believed that Edward was a homosexual because of his closeness to Gaveston, there is no concrete evidence of this. The king's enemies, including his cousin Thomas of Lancaster, captured and murdered Gaveston in 1312. The Great Famine of 1315–1317 may have resulted in half a million deaths in England due to hunger and disease, more than 10 per cent of the population.[77]

Edward's downfall came in 1326 when his wife, Queen Isabella, travelled to her native France and, with her lover Roger Mortimer, invaded England. Despite their tiny force, they quickly rallied support for their cause. The king fled London, and his companion since Piers Gaveston's death, Hugh Despenser, was publicly tried and executed. Edward was captured, charged with breaking his coronation oath, deposed and imprisoned in Gloucestershire until he was murdered some time in the autumn of 1327, presumably by agents of Isabella and Mortimer.

Edward III, son of Edward II, was crowned at age 14 after his father was deposed by his mother and Roger Mortimer. At age 17, he led a successful coup against Mortimer, the de facto ruler of the country, and began his personal reign. Edward III reigned 1327–1377, restored royal authority and went on to transform England into the most efficient military power in Europe. His reign saw vital developments in legislature and government—in particular the evolution of the English parliament—as well as the ravages of the Black Death. After defeating, but not subjugating, the Kingdom of Scotland, he declared himself rightful heir to the French throne in 1338, but his claim was denied due to the Salic law. This started what would become known as the Hundred Years' War.[78] Following some initial setbacks, the war went exceptionally well for England; victories at Crécy and Poitiers led to the highly favourable Treaty of Brétigny. Edward's later years were marked by international failure and domestic strife, largely as a result of his inactivity and poor health.

For many years, trouble had been brewing with Castile—a Spanish kingdom whose navy had taken to raiding English merchant ships in the Channel. Edward won a major naval victory against a Castilian fleet off Winchelsea in 1350.[79] Although the Castilian crossbowmen killed many of the enemy,[80] the English gradually got the better of the encounter. In spite of Edward's success, however, Winchelsea was only a flash in a conflict that raged between the English and the Spanish for over 200 years,[81] coming to a head with the defeats of the Spanish Armada and the English Armada in 1588 and 1589.[82][83] In 1373, England signed an alliance with the Kingdom of Portugal, which is claimed to be the oldest alliance in the world still in force. Edward III died of a stroke on 21 June 1377, and was succeeded by his ten-year-old grandson, Richard II. He married Anne of Bohemia, daughter of Charles IV, Holy Roman Emperor in 1382, and ruled until he was deposed by his first cousin Henry IV in 1399. In 1381, a Peasants' Revolt led by Wat Tyler spread across large parts of England. It was suppressed by Richard II, with the death of 1500 rebels.

Black Death

[edit]The Black Death, an epidemic of bubonic plague that spread all over Europe, arrived in England in 1348 and killed as much as a third to half the population. Military conflicts during this period were usually with domestic neighbours such as the Welsh, Irish, and Scots, and included the Hundred Years' War against the French and their Scottish allies. Notable English victories in the Hundred Years' War included Crécy and Agincourt. The final defeat of the uprising led by the Welsh prince, Owain Glyndŵr, in 1412 by Prince Henry (who later became Henry V) represents the last major armed attempt by the Welsh to throw off English rule.

Edward III gave land to powerful noble families, including many people of royal lineage. Because land was equivalent to power, these powerful men could try to claim the crown. When Edward III died in 1377, he was succeeded by his grandson, Richard II. Richard's autocratic and arrogant methods only served to alienate the nobility more, and his forceful dispossession in 1399 by Henry IV increased the turmoil. Henry spent much of his reign defending himself against plots, rebellions and assassination attempts. Rebellions continued throughout the first ten years of Henry's reign, including the revolt of Owain Glyndŵr, who declared himself Prince of Wales in 1400, and the rebellion of Henry Percy, 1st Earl of Northumberland. The king's success in putting down these rebellions was due partly to the military ability of his eldest son, Henry of Monmouth,[84] who later became king (though the son managed to seize much effective power from his father in 1410).

15th century – Henry V and the Wars of the Roses

[edit]| English Royalty |

| Second House of Lancaster |

|---|

|

| Henry IV |

Henry V succeeded to the throne in 1413. He renewed hostilities with France and began a set of military campaigns which are considered a new phase of the Hundred Years' War, referred to as the Lancastrian War. He won several notable victories over the French, including the Battle of Agincourt. In the Treaty of Troyes, Henry V was given the power to succeed the current ruler of France, Charles VI of France. The Treaty also provided that he would marry Charles VI's daughter, Catherine of Valois. They married in 1421. Henry died of dysentery in 1422, leaving a number of unfulfilled plans, including his plan to take over as King of France and to lead a crusade to retake Jerusalem from the Muslims.

Henry V's son, Henry VI, became king in 1422 as an infant. His reign was marked by constant turmoil due to his political weaknesses. While he was growing up, England was ruled by the Regency government. The Regency Council tried to install Henry VI as the King of France, as provided by the Treaty of Troyes signed by his father, and led English forces to take over areas of France. It appeared they might succeed due to the poor political position of the son of Charles VI, who had claimed to be the rightful king as Charles VII of France. However, in 1429, Joan of Arc began a military effort to prevent the English from gaining control of France. The French forces regained control of French territory. In 1437, Henry VI came of age and began to actively rule as king. To forge peace, he married French noblewoman Margaret of Anjou in 1445, as provided in the Treaty of Tours. Hostilities with France resumed in 1449. When England lost the Hundred Years' War in August 1453, Henry fell into mental breakdown until Christmas 1454.

Henry could not control the feuding nobles, and a series of civil wars known as the Wars of the Roses began, lasting from 1455 to 1485. Although the fighting was very sporadic and small, there was a general breakdown in the power of the Crown. The royal court and Parliament moved to Coventry, in the Lancastrian heartlands, which thus became the capital of England until 1461. Henry's cousin Edward, Duke of York, deposed Henry in 1461 to become Edward IV following a Lancastrian defeat at the Battle of Mortimer's Cross. Edward was later briefly expelled from the throne in 1470–1471 when Richard Neville, Earl of Warwick, brought Henry back to power. Six months later, Edward defeated and killed Warwick in battle and reclaimed the throne. Henry was imprisoned in the Tower of London and died there.

Edward died in 1483, only 40 years old, his reign having gone a little way to restoring the power of the Crown. His eldest son and heir Edward V, aged 12, could not succeed him because the king's brother, Richard III, Duke of Gloucester, declared Edward IV's marriage bigamous, making all his children illegitimate. Richard III was then declared king, and Edward V and his 10-year-old brother Richard were imprisoned in the Tower of London. The two were never seen again. It was widely believed that Richard III had them murdered and he was reviled as a treacherous fiend, which limited his ability to govern during his brief reign. In summer 1485, Henry Tudor, the last Lancastrian male, returned from exile in France and landed in Wales. Henry then defeated and killed Richard III at Bosworth Field on 22 August, and was crowned Henry VII.

Tudor period

[edit]

The Tudor period coincides with the dynasty of the House of Tudor in England that began with the reign of Henry VII. Henry engaged in a number of administrative, economic and diplomatic initiatives. He paid very close attention to detail and, instead of spending lavishly, concentrated on raising new revenues.[85][86] Henry was successful in restoring power and stability to the nation's monarchy following the civil war. His supportive policy toward England's wool industry and his standoff with the Low Countries had long-lasting benefit to the economy of England. He restored the nation's finances and strengthened its judicial system.[87] The Renaissance reached England, with a rich flowering of artistic, educational and scholarly debate from classical antiquity.[88] England began to develop naval skills, and exploration intensified in the Age of Discovery.[89][90] Historian John Guy (1988) posits that "England was economically healthier, more expansive, and more optimistic under the Tudors" than any time since the Roman occupation.[91]

England under the Tudor dynasty witnessed significant advancements in art, architecture, trade, exploration, and warfare, and commerce.[92] The term, "English Renaissance" is used by many historians to refer to a cultural movement in England in the 16th and 17th centuries. This movement is characterised by the flowering of English music (particularly the English adoption and development of the madrigal), notable achievements in drama, and the development of English epic poetry (most famously Edmund Spenser's The Faerie Queene).[93]

The English Renaissance also saw significant scientific progress. The astronomers Thomas Digges and Thomas Harriot made important contributions; William Gilbert published his seminal study of magnetism, De Magnete. He was the first to discover that the Earth was itself a dipole magnet as well as the first to correctly explain why a nautical compass worked as it did.[94] Human anatomy was revolutionised following the legalisation of human dissection by Henry VIII.[95] Observational science came of age when Thomas Digges recorded the first observation of a supernova.[96] A major English invention was the flush toilet by John Harington.[97] The invention of the knitting machine by William Lee was the first major stage in the mechanisation of the textile industry, a process that 200 years later led to the Industrial Revolution.[98] The perspective glass invented by Leonard Digges may have been the first telescope.[99] William Harvey founded human physiology.[100][101]

Substantial advancements were made in the fields of cartography and surveying. John Dee was the court astronomer for Elizabeth I and an influential mathematician, astronomer, astrologer, teacher, occultist, and alchemist. Francis Bacon was the pioneer of modern scientific thought, and is commonly regarded as one of the founders of the Scientific Revolution. His works were influential in the development of the scientific method.[102] Historian William Hepworth Dixon stated: "Bacon's influence in the modern world is so great that every man who rides in a train, sends a telegram, follows a steam plough, sits in an easy chair, crosses the channel or the Atlantic, eats a good dinner, enjoys a beautiful garden, or undergoes a painless surgical operation, owes him something''.[103][104]

Henry VII

[edit]

With the ascension of Henry VII to the throne in 1485, the Wars of the Roses concluded, ushering in a Tudor dynasty that would govern England for 118 years.[105] The Battle of Bosworth Field is traditionally viewed as the event that signified the end of the Middle Ages in England; however, Henry did not innovate the concept of monarchy, and his grip on power remained fragile for much of his reign. He asserted his claim to the throne through conquest and divine judgment in battle. Although Parliament swiftly acknowledged him as king, the Yorkist faction was not entirely vanquished. In January 1486, he strengthened his position by marrying Elizabeth, the eldest daughter of Edward IV, thereby uniting the rival houses of York and Lancaster. Many European monarchs doubted Henry's longevity on the throne, leading them to offer refuge to his challengers. The initial conspiracy against him was the Stafford and Lovell rebellion in 1486, which posed little danger. However, in the following year, John de la Pole, Earl of Lincoln and nephew of Richard III, orchestrated a more significant threat. He utiliSed a peasant boy named Lambert Simnel, who impersonated Edward, Earl of Warwick—who was imprisoned in the Tower of London—to rally an army of 2,000 German mercenaries financed by Margaret of Burgundy. This force was ultimately defeated at the challenging Battle of Stoke, where the loyalty of some of Henry's troops was in question. RecogniSing Simnel as a mere pawn, the king subsequently employed him in the royal kitchen.[106]

Perkin Warbeck, a Flemish youth who claimed to be Richard, the son of Edward IV, posed a significant threat to Henry VII. With the backing of Margaret of Burgundy, Warbeck attempted to invade England on four occasions between 1495 and 1497 before being captured and imprisoned in the Tower of London.[107] Both he and the Earl of Warwick remained threats even while incarcerated, leading to their execution in 1499, just prior to the marriage of Henry's son Arthur to Catherine of Spain. In 1497, Henry successfully quelled a rebellion by Cornish insurgents marching towards London. The remainder of his reign was largely stable, although concerns about succession arose following the death of his wife, Elizabeth of York, in 1503. Henry VII's foreign policy favoUred peace; he formed alliances with Spain and the Holy Roman Emperor Maximilian I. However, when these allies engaged in conflict with France in 1493, England was drawn into the war. Aware of his precarious position, Henry sought a swift resolution with France, relinquishing claims to all territories except Calais and acknowledging the inevitability of Brittany's incorporation into France. In exchange, the French recogniSed his kingship and ceased to harbour pretenders. Soon after, he shifted its focus to military endeavors in Italy. Additionally, Henry negotiated a marriage alliance with Scotland, promising his daughter Margaret to James IV.[108]

Upon becoming king, Henry inherited a government severely weakened and degraded by the Wars of the Roses. The treasury was empty, having been drained by Edward IV's Woodville in-laws after his death. Through a tight fiscal policy and sometimes ruthless tax collection and confiscations, Henry refilled the treasury by the time of his death. He also effectively rebuilt the machinery of government. He established peace with France in 1492, the Netherlands in 1496, and Scotland in 1499, leveraging his children's marriages to forge alliances across Europe. His commercial treaties and encouragement of trade significantly enhanced England's wealth and power. In 1501, the king's son Arthur, having married Catherine of Aragon, died of illness at age 15, leaving his younger brother Henry, Duke of York as heir. When the king himself died in 1509, the position of the Tudors was secure at last, and his son succeeded him unopposed.[109]

Henry VIII

[edit]

Henry VIII began his reign with much optimism. Known for his flamboyance, vigor, militaristic nature, and strong will, stands out as one of England's most prominent monarchs, largely due to his six marriages aimed at securing a male heir and his severe actions against numerous high-ranking officials and nobles. He crafted the persona of a Renaissance man, transforming his court into a hub of intellectual and artistic advancement, with opulent displays such as the Field of the Cloth of Gold. Upon ascending the throne, he inherited a substantial fortune and a thriving economy from his frugal father, with the wealth estimated at £1,250,000, equivalent to approximately £375 million today. He married the widowed Catherine of Aragon, and they had several children, but none survived infancy except a daughter, Mary.[110]

He was most notably recognised for his turbulent romantic relationships and the founding of the Church of England. Additionally, he played a significant role in the formation of the Royal Navy, promoting shipbuilding and the development of dockyards.[111] In 1512, the young king started a war in France. Although England was an ally of Spain, one of France's principal enemies, the war was mostly about Henry's desire for personal glory, despite his sister Mary being married to the French king Louis XII. Meanwhile, James IV of Scotland (despite being Henry's other brother-in-law), activated his alliance with the French and declared war on England. While Henry was dallying in France, Catherine, who was serving as regent in his absence, and his advisers were left to deal with this threat. At the Battle of Flodden on 9 September 1513, the Scots were completely defeated. James and most of the Scottish nobles were killed. When Henry returned from France, he was given credit for the victory.[112]

Eventually, Catherine was no longer able to have any more children. The king became increasingly nervous about the possibility of his daughter Mary inheriting the throne, as England's one experience with a female sovereign, Matilda in the 12th century, had been a catastrophe. He eventually decided that it was necessary to divorce Catherine and find a new queen. To persuade the Church to allow this, Henry cited the passage in the Book of Leviticus: "If a man taketh his brother's wife, he hath committed adultery; they shall be childless". However, Catherine insisted that she and Arthur never consummated their brief marriage and that the prohibition did not apply here. The timing of Henry's case was very unfortunate; it was 1527 and the Pope had been imprisoned by emperor Charles V, Catherine's nephew and the most powerful man in Europe, for siding with his archenemy Francis I of France. Because he could not divorce in these circumstances, Henry seceded from the Church, in what became known as the English Reformation.[113]

The newly established Church of England amounted to little more than the existing Catholic Church, but led by the king rather than the Pope. It took a number of years for the separation from Rome to be completed, and many were executed for resisting the king's religious policies. In 1530, Catherine was banished from court and spent the rest of her life (until her death in 1536) alone in an isolated manor home, barred from contact with Mary. Secret correspondence continued thanks to her ladies-in-waiting. Their marriage was declared invalid, making Mary an illegitimate child. Henry married Anne Boleyn secretly in January 1533, just as his divorce from Catherine was finalised. They had a second, public wedding. Anne soon became pregnant and may have already been when they wed. But on 7 September 1533, she gave birth to a daughter, Elizabeth. The king was devastated at his failure to obtain a son after all the effort it had taken to remarry. Gradually, he came to develop a disliking of his new queen for her strange behaviour. In 1536, when Anne was pregnant again, Henry was badly injured in a jousting accident. Shaken by this, the queen gave birth prematurely to a stillborn boy. By now, the king was convinced that his marriage was hexed, and having already found a new queen, Jane Seymour, he put Anne in the Tower of London on charges of witchcraft. Afterwards, she was beheaded along with five men (her brother included) accused of adultery with her.[114]

Henry immediately married Jane Seymour, who became pregnant almost as quickly. On 12 October 1537, she gave birth to a healthy boy, Edward, which was greeted with huge celebrations. However, the queen died of puerperal sepsis ten days later. Henry genuinely mourned her death, and at his own passing nine years later, he was buried next to her. The king married a fourth time in 1540, to the German Anne of Cleves for a political alliance with her Protestant brother, the Duke of Cleves. He also hoped to obtain another son in case something should happen to Edward. Anne proved a dull, unattractive woman and Henry did not consummate the marriage. He quickly divorced her, and she remained in England as a kind of adopted sister to him. He married again, to a 19-year-old named Catherine Howard. But when it became known that she was neither a virgin at the wedding, nor a faithful wife afterwards, she ended up on the scaffold and the marriage declared invalid. His sixth and last marriage was to Catherine Parr, who was more his nursemaid than anything else, as his health was failing since his jousting accident in 1536.

In 1542, the king started a new campaign in France, but unlike in 1512, he only managed with great difficulty. He only conquered the city of Boulogne, which France retook in 1549. Scotland also declared war and at Solway Moss was again totally defeated. Henry's paranoia and suspicion worsened in his last years. The number of executions during his 38-year reign numbered tens of thousands. His domestic policies had strengthened royal authority to the detriment of the aristocracy, and led to a safer realm, but his foreign policy adventures did not increase England's prestige abroad and wrecked royal finances and the national economy, and embittered the Irish.[115] He died in January 1547 at age 55 and was succeeded by his son, Edward VI.[116]

Father of the Royal Navy

[edit]

The Tudor navy represented the naval force of the Kingdom of England during the Tudor dynasty, a period marked by significant transformations that established a permanent naval presence and set the groundwork for the future Royal Navy. Historian J.J. Scarisbrick attributes the title of "Father of the English navy" to Henry VIII, who regarded the navy as a personal instrument of power.[117]

He inherited seven small warships from his father and expanded the fleet to twenty-four vessels by 1514. By March 1513, he observed his formidable fleet, commanded by Sir Edmund Howard, as it navigated the Thames, comprising 24 ships, including the 1600-ton "Henry Imperial," and carrying 5,000 marines and 3,000 sailors. This force successfully repelled the French fleet, secured the English Channel, and blockaded Brest. Henry VIII was the first monarch to establish the navy as a permanent entity with a structured administrative and logistical framework funded by taxation. While focusing on land initiatives, he founded royal dockyards, initiated shipbuilding forestry, enacted navigation laws, fortified the coastline, established a navigation school, and defined the roles of naval personnel. He meticulously oversaw the design and construction of his warships, understanding their specifications and combat strategies, while also promoting advancements in naval architecture, such as the Italian method of gun placement that improved stability. His attention to detail was evident, particularly during the ceremonial launch of new ships.[118]

Edward VI

[edit]

Although he showed piety and intelligence, Edward VI was only nine years old when he became king in 1547.[115] Edward Seymour, 1st Duke of Somerset and uncle to Henry VIII, manipulated the king's will and secured letters patent that granted him significant monarchical powers by March 1547. He assumed the title of Protector, and while some regarded him as an idealist, his tenure ended in turmoil during the 1549 crisis marked by widespread protests across various counties. Notable uprisings, such as Kett's Rebellion in Norfolk and the Prayer Book Rebellion in Devon and Cornwall. Disliked by the Regency Council for his autocratic style, Somerset was ultimately ousted by John Dudley, known as Lord President Northumberland, who then took control with a more conciliatory approach that the Council accepted. Under Edward's rule, England transitioned from Catholicism to Protestantism, severing ties with Rome.[119]

Edward showed great promise but fell violently ill of tuberculosis in 1553 and died that August, at the age of 15 years, 8 months.[115] Northumberland made plans to place Lady Jane Grey on the throne and marry her to his son, so that he could remain the power behind the throne. His plot failed in a matter of days, Jane Grey was beheaded, and Mary I (1516–1558) took the throne amidst popular demonstration in her favour in London, which contemporaries described as the largest show of affection for a Tudor monarch.

Mary I

[edit]

Mary I was the first Queen Regnant, meaning she ruled in her own right rather than through marriage. An Act of Parliament in 1533 had declared her illegitimate, stripping her of her claim to the throne, although she was reinstated in 1544, only to be removed again by her half-brother Edward shortly before his death. During her reign, she faced pressure to abandon the Mass and accept the English Protestant Church. Mary reinstated papal authority in England, relinquished the title of Supreme Head of the Church, reintroduced Roman Catholic bishops, and began the gradual restoration of monastic orders. She also revived heresy laws to enforce religious conformity, equating heresy with treason, which led to the execution of approximately 300 Protestant heretics within three years, including notable figures like Cranmer, Latimer, and Ridley, alongside many impoverished individuals. This harsh treatment not only rendered Mary unpopular but also highlighted the commitment of individuals to the Protestant faith established during Henry's reign.[120]

The advancement of Mary's religious agenda was further hindered by the interests of the aristocracy and gentry, who had acquired monastic lands during the Dissolution of the Monasteries and were unwilling to relinquish them as Mary requested. At the age of 37 upon her accession, Mary sought to marry and bear children to secure a Roman Catholic heir and eliminate her half-sister Elizabeth from the line of succession, as Elizabeth represented a focal point for Protestant resistance. Mary had never been expected to hold the throne, at least not since Edward was born.[121] As queen, she promoted trade and exploration while reforming the taxation system.[122]

Mary then married her cousin Philip, son of Emperor Charles V, and King of Spain when Charles abdicated in 1556. The union was difficult because Mary was already in her late 30s and Philip was a Catholic, and so not very welcome in England. This wedding also provoked hostility from France, already at war with Spain and now fearing being encircled by the Habsburgs. King Philip had very little power, although he did protect Elizabeth. He was not popular in England, and spent little time there.[123] Mary eventually became pregnant, or at least believed herself to be. In reality, she may have had uterine cancer. Her death in November 1558 was greeted with huge celebrations in the streets of London.[124]

Elizabeth I

[edit]

After Mary I died in 1558, Elizabeth I came to the throne. Her reign restored a sort of order to the realm after the turbulent reigns of Edward VI and Mary I. The religious issue which had divided the country since Henry VIII was in a way put to rest by the Elizabethan Religious Settlement, which re-established the Church of England. Much of Elizabeth's success was in balancing the interests of the Puritans and Catholics; historian Robert Bucholz paraphrasing historian Conrad Russell, suggested that the genius of the Church of England was that it "thinks Protestant but looks Catholic."[115] She managed to offend neither to a large extent, although she clamped down on Catholics towards the end of her reign as war with Catholic Spain loomed.[125][126]

Despite the need for an heir, Elizabeth declined to marry, despite offers from a number of suitors across Europe, including the Swedish king Erik XIV. This created endless worries over her succession, especially in the 1560s when she nearly died of smallpox. It has been often rumoured that she had a number of lovers (including Francis Drake). Significant accomplishments during the reign of Elizabeth I encompass the triumph over the Spanish Armada in 1588, which established England's dominance at sea, as well as the promotion of a vibrant cultural atmosphere that enabled English literary and music to thrive.[127] Elizabeth's initiatives resulted in the Religious Settlement, a legal framework that reinstated the Protestant Church of England, with the queen assuming the title of Supreme Governor of the Church of England.[128]

Elizabeth maintained relative government stability. Apart from the Revolt of the Northern Earls in 1569, she was effective in reducing the power of the old nobility and expanding the power of her government. Elizabeth's government did much to consolidate the work begun under Thomas Cromwell in the reign of Henry VIII, that is, expanding the role of the government and effecting common law and administration throughout England. During the reign of Elizabeth and shortly afterwards, the population grew significantly: from three million in 1564 to nearly five million in 1616.[129] The queen ran afoul of her cousin Mary, Queen of Scots, who was a devoted Catholic and so was forced to abdicate her throne (Scotland had recently become Protestant). She fled to England, where Elizabeth immediately had her arrested. Mary spent the next 19 years in confinement, but proved too dangerous to keep alive, as the Catholic powers in Europe considered her the legitimate ruler of England. She was eventually tried for treason, sentenced to death, and beheaded in February 1587.[130]

In foreign policy, Elizabeth played against each other the major powers France and Spain, as well as the papacy and Scotland. These were all Catholic and each wanted to end Protestantism in England. Elizabeth was cautious in foreign affairs and only half-heartedly supported a number of ineffective, poorly resourced military campaigns in the Netherlands, France and Ireland. She risked war with Spain by supporting the "Sea Dogs", such as Walter Raleigh, John Hawkins and Sir Francis Drake, who preyed on Spanish merchant ships carrying gold and silver from the New World. Drake himself became a hero—being the first Englishman to circumnavigate the world between 1577 and 1580, having plundered Spanish settlements and treasure ships.[131] The war ended with both sides seeking peace in order to stop the costly conflict with the Treaty of London in 1604, which validated the status quo ante bellum.[132][133] It amounted to an acknowledgement by Spain that its hopes of restoring Roman Catholicism in England were at an end and it had to recognise the Protestant monarchy in England. In return, England ended its financial and military support for the Dutch rebellion, ongoing since the Treaty of Nonsuch (1585), and had to end its wartime disruption of Spanish trans-Atlantic shipping and colonial expansion.

Following the voyages of Christopher Columbus, which captivated Western Europe, England embarked on its own colonisation efforts in the New World. In 1562, Queen Elizabeth I dispatched privateers to capture treasure from Spanish and Portuguese vessels off West Africa's coast. While Spain had firmly established its presence in the Americas and Portugal, allied with Spain since 1580, maintained an expansive empire across Africa, Asia, and South America, France was actively exploring North America. This competitive landscape motivated England to focus on establishing colonies, particularly in the West Indies rather than North America. Sir Francis Drake's circumnavigation of the globe from 1577 to 1580, along with his audacious attacks on Spanish ships and a significant victory at Cadiz in 1587, elevated him to national hero status. In 1583, Humphrey Gilbert claimed Newfoundland, asserting control over the harbour of St. John’s and the surrounding lands. In 1600, the queen also chartered the East India Company, which laid the groundwork for future trading posts that would eventually develop into British India along the coasts of present-day India and Bangladesh. The larger-scale colonization efforts commenced shortly after Elizabeth's passing.[134]

The Tudor period is regarded as a pivotal era that raised significant questions to be addressed in the subsequent century and throughout the English Civil War. These inquiries revolved around the balance of power between the monarchy and Parliament, particularly regarding their respective controls. Some historians assert that Thomas Cromwell initiated a "Tudor Revolution" in governance, noting that Parliament gained prominence during his time as chancellor. Conversely, other historians contend that this "Tudor Revolution" continued until the conclusion of Elizabeth's reign, when the changes were fully integrated. While the Privy Council's influence waned after Elizabeth's passing, it functioned effectively during her lifetime. Elizabeth died in 1603 at the age of 69.[135]

Elizabethan era

[edit]

The Elizabethan era marks a significant period in English history, corresponding to the reign of Queen Elizabeth I from 1558 to 1603. This period is frequently noted by historians as a golden age in England's history. The emblem of Britannia was first introduced in 1572 and subsequently became a representation of the Elizabethan age, symbolising a renaissance that fostered national pride through classical ideals, overseas expansion, and naval victories against the formidable Spanish adversary.[136] This "golden age" epitomised the zenith of the English Renaissance, witnessing a flourishing of poetry, music, and literature. The era is particularly renowned for its theatrical achievements, with William Shakespeare and numerous contemporaries creating plays that transcended the traditional styles of English theatre. The increasing population, rising affluence, and enthusiasm for entertainment among the English people contributed to a dramatic literature of exceptional quality. The English theatre landscape, catering to both the court and nobility through private performances as well as a broad public audience in theatres, became the most vibrant in Europe.[137]

During the reign of Elizabeth I, there was a significant enhancement in crafts and manufacturing sectors. The glass, ceramic, and silk industries, along with the exportation of goods, experienced notable promotion. Economically, the establishment of the Royal Exchange by Sir Thomas Gresham in 1565, which marked the inception of the first stock exchange in England and one of the earliest in Europe, represented a crucial advancement for England's economic landscape and eventually for the global economy. With tax rates lower than those in other European nations at the time, the economy witnessed substantial growth; by the conclusion of Elizabeth's reign, there was evidently more wealth distributed than at its commencement. This era of general peace and prosperity fostered the remarkable developments characteristic of the "golden age." The Elizabethan period is renowned for its playwrights who flourished during this time, as well as for figures such as Francis Drake, the first Englishman to complete a circumnavigation of the globe (and the third person overall), and Walter Raleigh's ventures into the New World. The stability and organisation of the government facilitated the flourishing of the arts and encouraged further achievements in exploration.[138]

The rise in population, the establishment of joint-stock companies, the expansion of private enterprise, advancements in banking, the development of trade routes, and innovations in manufacturing significantly enhanced commercial activities in England. Consequently, England strengthened its naval power and established numerous merchant joint-stock companies and institutions. The first joint-stock company established in England was the Company of Merchant Adventurers to New Lands, which was founded in 1551 and comprised 240 shareholders. This company evolved into the Muscovy Company after receiving a royal charter in 1555, granting it a monopoly on trade between Russia and England. Among the most significant joint-stock companies was the East India Company, which received a royal charter from Elizabeth I on December 31, 1600, aimed at facilitating trade in the Indian subcontinent. This charter conferred upon the newly established Honourable East India Company a fifteen-year monopoly over all English trade in the East Indies. By the mid-1700s and early 1800s, the company had come to represent half of the global trade. The expansion of English naval power and the growing interest in exploration contributed to the establishment and colonisation of overseas territories, particularly in North America and the Caribbean.[139][140]